HOW DID THE GARIFUNA BECOME AN INDIGENOUS PEOPLE? - RECONSTRUCTING THE CULTURAL PERSONA OF AN AFRICAN-NATIVE AMERICAN PEOPLE IN CENTRAL AMERICA

However, anthropology has been forced to come to terms with the realities of the modern world in which displaced identities and recuperated identities go to form what has been called a global ethnoscape.

Neil Whitehead (1998).

RESUMEN: ¿Cómo fue que los Garifuna adquirieron el estatus de indígenas? Reconstrucción de la persona cultural de los nativos de Centroamérica. El título del artículo aquí presentado pretende llamar la atención al relativo reciente origen la nomenclatura “indígena” en referencia a nativos del Nuevo Mundo. Los Garifuna –grupo indígena conformado a partir dela mezcla entre nativos americanos, africanos y el carácter bio-cultural legado por los europeos – constituyen un tópico adecuado para el estudio de la formación y retención de la identidad cultural en la revoltura caribeña. Esta presentación inicia destacando la formación de la matriz cultural en el tiempo y el espacio dentro de un contexto en el que la sabiduría convencional que detentaban los pueblos originarios fue exterminada. Continua, haciendo referencia a la creación de oportunidades por parte de los Garifuna para consolidar su identidad en el Caribe oriental a partir de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, en que se suscitaron décadas de conflicto armado impuesto sobre ellos por los británicos. Termina, con citas de ejemplos de vida del mismo autor relativas a su activismo en los ámbitos académico y movimiento popular indígena en Belice, su país de origen, desde el inicio de la década de 1970.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Garifuna, indígena, identidad.

ABSTRACT: The title of this presentation draws attention to the relatively recent origins of the ‘indigenous’ nomenclature to the persona of indigenous peoples in the New World. The Garifuna – an indigenous people formed from the blending of Native American, African, and European bio-cultural traits – are an appropriate topic for the study of the formation and retention of cultural identity within the Caribbean Basin. This presentation starts with the formation of their cultural matrix over time and space within a context, where conventional wisdom held that all native peoples had been exterminated. It continues with the Garifuna creating opportunities for the consolidation of their identity in the Eastern Caribbean during the latter of half of the nineteenth century, within decades of armed conflict imposed on them by the British. It ends by the author citing examples from his own involvement in academic and popular activism within the indigenous people movement in his home country Belize since the early 1970s.

KEY WORDS: Garifuna, indigenous, identity.

Introducción

The reason for asking the question: “How did the Garifuna become an indigenous people?” Is that they are black within a region, highly conscious of skin color, that ascribes indigenous identity only to persons with olive skin color. This question of skin will always problematic, specially in the perception of other indigenous people, who have accused the Garifuna of usurping an identity that is not truly theirs.1

Another reason to ask the question is to understand how the Garifuna have maintained continuity in their identity in the face of destructive experiences, each of which could have derailed them from the track of being one people with one identity. These experiences include migration across large areas in northeast South America, spilling over into the Eastern Caribbean, systematic genocide in St. Vincent, massive displacement across hundreds of kilometers in the Atlantic Ocean, and over 200 years of pervasive racial discrimination in Central America leading many persons to forsake their cultural identity altogether and join the majority within their respective societies.

The short answer to the question how did the Garifuna become indigenous is that they added the label “indigenous” onto themselves when they and other bio-cultural groups of Native American descent within the Circum-Caribbean acquired the generic term in the late 1980s. Beforehand, these people, also called Amerindians, had used their own traditional names, such as Maya, Kekchi, and Garifuna. The acceptance of “indigenous” came through the influence of indigenous activists in the political movement originating in North and Central America. One regional indicator was the formation in 1989 of the Caribbean Organization of Indigenous Peoples (COIP) by peoples in the former British colonies from Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, St. Vincent, Dominica, and Belize (Palacio 2006: 215-234). The larger global validation came in 1992 when the COIP was accepted as member organization of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP) (Palacio 2006: 215-234). The use of the designation “indigenous peoples” has been refined by multilateral agencies including the United Nations and the Organization of American States.

This essay follows on the theme of this gathering – “An inquiry into the notion of persona – reconstructing the notion of persona in Mexico and Central America” – with a focus on the Garifuna. I aim to amplify the scope of reconstructing cultural identity in three ways. Firstly, I trace the formation of the cultural matrix of an indigenous people over several hundred years and several hundred square kilometers. Secondly, I accentuate the efforts of the people to consistently retain their cultural identity, while taking advantage of opportunities available in the larger society. Thirdly, I integrate my own experiences in the consolidation of Garifuna peoplehood in Belize within the past thirty years.

There is implicit in this essay the spirit of an odyssey that starts with the trajectory of a people and ends as my own personal experience as scholar and activist among indigenous peoples. This paper is still very much a work in progress. I thank the organizers of this gathering whose initiative has helped me to sharpen my focus on the definition and formation of social and cultural identity among a people, who have faced overwhelming odds for thousands of years. I am grateful for questions and comments as

I move forward.

It is impossible to arrive at an accurate population figure for all the Garifuna because of the tremendous geographical spread across four countries within the northeast coast of Central America and their dispersion within North American cities, such as New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New Orleans. The figure normally quoted is about 300,000. The largest proportion lives in Honduras with additional numbers in Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua (see Fig. 1). In these countries they have settled for a little over 200 years initially in dozens of coastal small villages, many of which are being overrun by ladino immigrants displaced from their own hinterland communities. In response the Garifuna are moving in larger numbers to coastal towns, such as Puerto Cortez, Tela, La Ceiba in Honduras and Belize City in Belize, as well as further away into North American cities.

The current process of urbanization is probably generating the greatest threat to the survival of the Garifuna as a socio-cultural unit, which previously had always been dispersed in small, kinship based rural communities. The longevity of Garifuna culture as we know it has been due to its incubation within small villages all along the coast of Central America for the better part of the last 200 years.

Fig. 1 Map of the Circum-Caribbean Area (copied from Palacio 2005:8, courtesy of Cubola Press).

Despite their relatively small population size the Garifuna have been hosts to several ethnographers, since the 1950s. Douglas Taylor, Nancie Gonzalez, Virginia Kerns, Catherine Macklin, Mark Moberg, Byron Foster, Carol Jenkins, Alfonso Arrivillaga, and William Davidson are only a few from the large body of visiting anthropologists.

Additionally there are several Garifuna men and women, who have written works about their own people; most of which have remained unpublished. They include Sebastian Cayetano, Marion Cayetano, Roy Cayetano, Jorge Bernardez, Felicia Hernandez, Joseph Palacio, Myrtle Palacio, Godsman Ellis, Zoila Ellis, Salvador Suazo, and Virgilio Lopez Garcia. The relatively large numbers of native scholars within the Garifuna population, a large part of which still remains at limited levels of literacy, indicates a strong dedication to unravel the story of their people through the written word. But there is a large body of oral literature that is unrecorded and still needs to be captured.

The published data about the Garifuna falls into the categories of history and contemporary issues. The topic of cultural identity, which is the theme of this gathering, is pervasive within both of these categories. One of the most comprehensive analyses of the history of cultural identity is Nancie Gonzalez’s 1988 volume on ethnohistory and ethnogenesis. She traces the historical formation of the Garifuna and uses the configuration of select traits to identify their ethnic identity in coastal Central America. Taking a parallel approach – also based on coastal Central America – has been the interest of mainly Garifuna students on genealogy, more specifically on first settlers of given localities and subregions by family groups (Arrivillaga 2005: 64-84). Both Davidson (1980: 31-62) and Palacio (2005: 43-63) have extended their genealogical reconstruction as far as families in St. Vincent.

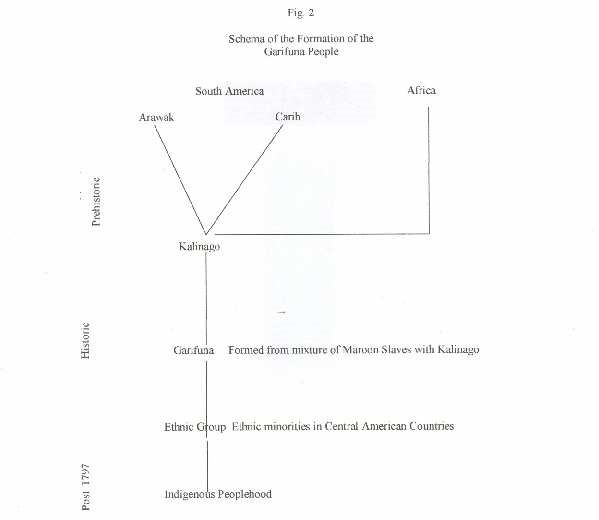

Indeed, it is tempting to peel back the layers of the Garifuna persona through time and space from South America and West Africa through the Eastern Caribbean and their eventual arrival in Central America. Such effort awaits the work of scholars in history and anthropology. However, it is possible to outline a schema, as I have done in Fig. 2, which could be the skeleton of such a longitudinal reconstruction.

The schema has three parts – the pre-St. Vincent, St. Vincent, and post-St.

Vincent periods. The pre-St. Vincent part covers both the prehistoric period in northeast South America and

West Africa together with the historic period centering on the efforts of the Island Caribs to wrest control

of their former East Caribbean subregion from the British and French. The St. Vincent period starts from the

mid-seventeenth century and ends with the exile to Central America in 1797. The post-St. Vincent period

extends from 1797 to the present.

Fig. 2: Schema of the Formation of the Garifuna People

Within the scheme in Fig. I attempt to retrace the building of a pre-Garifuna identity and follow major episodes in its transformation to the state that we know it in today. Whereas the core traits that the modern day Garifuna people can claim as theirs originated in northeastern South America and West Africa, the congealing of the overall culture to its present stage took place in St. Vincent. Afterwards, the people have opposed being relegated to an ethnic group in their Central American states because of an ideology of people hood that resonates with their original status as sovereign nation in St. Vincent.

If the Garifuna culture has been a cumulative body of various sub-cultures, is there a place or a point in time that marked the genesis of its cultural matrix?

While we can be certain about the broad parameters of the location, we can be less precise about the time. The location was the Orinoco River basin, which cuts the map of Venezuela into two parts running in an east-west axis. Because of the overlap among cultures extending south of the Orinoco, Neil Whitehead (1988: 9-20) uses the name “Guayana” for the larger subregion extending from the Orinoco to the Amazon River. Furthermore, this confirms the designation Amazon Rainforest Tradition as the cultural matrix of the ancestors of the Garifuna. In narrowing the location of genesis, we refer to the part of the Orinoco River basin nearest to the Caribbean islands into which the Garifuna ancestors dispersed. The island of Trinidad is located a short distance north of the delta of the Orinoco and further south along the Atlantic Ocean are the Guianas. Presently located in French Guiana and Suriname are the Galibi Karinya, who were culturally related to the Island Caribs. Some anthropologists affirm that the Galibi were precursors of the Island Caribs (Allaire 1997: 177-185).

The question when the cultural matrix started falls to the archaeologists and diachronic linguists and in both areas there is great uncertainty. We are safe in saying that it would have been earlier than 2000 B.C., the earliest time marker for habitation in the Caribbean islands, although it cannot be said with certainty that these pioneer settlers originated on the South American mainland (Rouse 1992). Needless to say, there is also doubt as to who these pioneers were. Of more importance than name designations were the larger set of preconditions that facilitated the welding of peoples who eventually became the Island Caribs. The Orinoco River basin is replete with a wide variety of small and large microenvironments producing riverine, terrestrial, and coastal resources that could be exploited and traded (Whitehead 1988: 7-20). After centuries of these reciprocal exchanges the Karinya emerged among the more dominant groups, who were able to command a

greater share of the resources. As in the other cases of reconstructing a history with many unknowns, it is safer to conclude that along with the Karinya there were other groups with similarities in language, belief systems, and material culture; and that they formed alliances for their mutual well-being. From such an overlap came groups who crossed at various time periods into the Caribbean islands.

It is worth emphasizing a caveat that will be recurring in further discussions that ascribing place names to groups living within overlapping geographical subregions is not fruitful. Holdren (1998: 1-8) refers to the dilemma that ethnonyms can create in the historical description of groups in the Caribbean.

The discussion so far has referred to the prehistoric pre-St. Vincent period. Taking place simultaneously across the Atlantic in West Africa would have been another set of factors consolidating groups, who would eventually travel to the New World first as free men on exploratory missions and later in much greater numbers as slaves. There has not been any attempt at a chronological coordination about events taking place among groups on both sides of the Atlantic, whose descendants would eventually join to become the Garifuna nation in St. Vincent. Both, the origins of Africans and their intermixture with the Island Caribs, who ended up in the Eastern Caribbean are little understood in Garifuna history and are awaiting much needed research.

The next stage in the prehistoric pre-St. Vincent period was the movement and consolidation of the descendants of the Orinoco River Basin peoples, who came to be known as the Island Caribs or Caraibe, the term that Holdren (1998) prefers.

The adjective ‘Island’ differentiates them from the mainland Caribs, who remained in South America. There is agreement that if they had left the mainland as separate tribal groups, they narrowed many of their differences as they formed a “confederacy” of “politically autonomous” groups (Holdren 1998), extending from Grenada in the south to the Virgin Islands in the north. The amalgamation came from their opposition to European colonization resulting in recurring warring expeditions by men drawn from the islands as well as from their allies on the South American mainland.

While there was scant information about the cultures of the Orinoco River Basin period, what they traded and with whom, and the level of complexity in their social structures, there is much information available about the Island Carib period originating in reports by French missionaries and the archives of colonial authorities. Interestingly, one of the most knowledgeable about this period, Louis Allaire (1997: 177-185) gave much credit to the statements of the Island Caribs themselves that they reportedly gave to Columbus and his chroniclers. Based on the documentary sources available, Allaire concludes that by the mid 17th century they had a strong identity characterized by traits, such as the women’s ornamental wear and drinking manioc beer (not done by the Arawaks). Allaire (1997: 180) adds “…. they shared a strong national character and ethnic identity. They claimed openly that they were of the same ethnicity as their Carib neighbors of what is today French Guiana and Suriname.”

A defining characteristic of the Island Carib was their use of multiple languages even within their own community and household. According to Cooper (1997: 186-196) women used Island Carib when speaking to their male peers and Arawak with their children and other women. On the other hand, the male children spoke Island Carib to their fathers. Among themselves the men used a Carib based pidgin, which was a widespread trading language in South America (Allaire 1997: 177-185). This pidgin resulted from centuries of trading intermittent warfare between mainland Caribs and several other tribes. In an illuminating article Cooper (1997: 186-196) has analyzed the differences that existed between women’s and men’s speech, some of which still exist in modern day Garifuna society.

We can summarize what we know about the descendants of the mainland Caribs, who originated within the Orinoco River Basin and had started their island hopping probably as far back at least as 2000 B.C. By the end of the 17th century A.D. they had a strong cultural identity that had been tested several times in several wars against other native tribes and subsequently against Europeans.

The French and British had suffered so much from their guerrilla raids that both agreed in 1686 and again in 1748 that Dominica and St. Vincent (see Fig. 1), the two subcapitals of Carib aggression, should remain as neutral territories for either side. In other words, they would be sanctuaries for the Caribs within a region becoming the colonial territory of either Britain or France. Island Caribs have become stereotyped as a aggressively warfaring people, however we need to consider their strong role in trade in which they have engaged from their early mainland era and received much impetus through the introduction of European trade goods. As in their war effort, trading necessitated covering long distances over land and ocean, accumulating much needed skills in boat building, navigation, and negotiation with different sets of peoples across several cultures on everything, from pathways to buying and selling trade items. They had acquired remarkable proficiency in a grate variety of situations across space and time, demonstrating an uncanny skill in predicting reactions and exploiting them in their own benefit.

As people with enduring spirituality they had adjusted their long held mainland iconography to the ecology of the islands. In a highly reflective essay Honychurch (2002) has traced how they incorporated new island images, such as the summits of volcanic mountain outcrops, as symbols for their deity.

Similarly, they could no longer hunt larger mammals in the islands, such as tapir and jaguar, that had been available on the mainland. Instead they fashioned traps to catch smaller game animals. Finally, they adjusted traditional ceremonies to mark the annual seasons that were slightly different in the islands.

The cultural plurality, already so well established among the Island Caribs, took on added ingredients from groups arriving after Columbus. Europeans intermarried with their women notably in Dominica and St. Vincent. If these marriages were of a predatory nature where white men took advantage of native women, there was also another type of intermarriage initiated by men escaping slavery and desperately in need of refuge within a host community. These were maroon African slaves escaping from plantations in nearby islands, and especially taking advantage of refuge after Dominica and St. Vincent had been declared neutral islands.

The intermarriage of Africans and Caribs took place extensively throughout the Eastern Caribbean and the entire archipelago. The fusion between the two parties taking place in St. Vincent was unique insofar as there was a consolidation into a cultural matrix with a sustained past and continuity up to the present. Among corresponding intermixtures in other islands this level of welding has not endured.

While there have been distinct cultures formed from the mixture of Africans with Native Americans in other parts of the Americas, notably Brazil (Bastide 1972), the only example in the Circum-Caribbean is the Garifuna. The following description of the St.

Vincent era explains further the process of consolidation.

The next period in the schema in Fig. 2 takes place in the island where the Garifuna, the name the Black Caribs use for themselves, were formed. There is more literature available on this period from a wider variety of sources than for the previous periods we have reviewed. In addition to the traditional British sources, such as (Young 1971), there is the account by Kirby and Martin (1972), which presents a perspective that is as close as one can get to the Garifuna viewpoint. There are also French sources that present a humanist perspective highlighting their interactions with the residents of St. Vincent (Hulme 2005: 21-42). Curtis Jacobs’ essay (2003) gives a view of the French records about the 1794-1796 Brigands War, also called the Second Carib War. Unfortunately, there seem to be even fewer accounts of the culture than what had been available from French missionaries in the previous era.

Regrettably we thus know much more about their fighting with the French and British than about the things they did in their daily life. Unknown therefore is much about the culture that eventually arrived in Central America.

The Island Carib supremacy of the Eastern Caribbean of Pre-Columbian times was bound to dissipate in the face of the superior military might of the British and French. By 1700 Dominica and St. Vincent had become little more than symbolic vestiges of a previous regional domain in the hands of indigenous people. This essay concerns with how this end would take place; would the Garifuna be able to preserve themselves as a socio-culture or would they hemorrhage to the point of gradual extinction as had happened to others throughout the Circum-Caribbean earlier and would continue to do so later.

The end of the hegemony came about as a protracted attrition of rights to natural resources. As a result, the Garifuna lost their natural resources but in the process consolidated their nationhood and their persona as a people. Europeans firstly denuded the forest of St. Vincent and secondly acquired all lands that belonged to the Garifuna. By 1700 Barbados with a land area of only 451 square kilometers already was severely overcrowded with a population of over 65,000 (Beckles 1990: 42). To satisfy the need for fuel as well as timber for construction, the British had long looked to St. Vincent located a mere one hundred and forty kilometers to the west. Further environmental degradation came with the overflow of French and British colonists who clear-cut forests, while introducing their domestic animals. In the advance of these incursions the remaining Caribs and Black Caribs were forced to relocate to the more remote portions of the leeward side of the island. In the end they encountered ever greater difficulty to retain their traditional system of living with the land in reverence to the wishes of their ancestors and as stewards for the next generations (Miller 1979: 79)

The larger numbers of arriving maroon slaves and the correspondingly declining numbers of yellow Caribs might have been by themselves sufficient reasons for the welding of the Blacks and Yellows to form the indissoluble Garifuna socio-culture. But taking place was also a struggle for sovereign control of the island, which became a political conflict between the Garifuna and the British, around which the French and Garifuna formed an alliance against the British as their common enemy. While the Garifuna fought for the land that was their patrimony as a nation, the French were fighting for the same land to claim as their colonial possession. Archival information that Jacobs retrieved from French archives are most revealing in tracing the various machinations of master Brigand2 Victor Hughes to bring St. Vincent under French control, although the colonial ambitions in Paris durung that time had weakened, as there was much more focus on domestic rehabilitation after the disastrous French Revolution.

The diverging reasons for the collaboration between the Garifuna and French are summarized by Jacobs, “Hughes, however, was the representative of a country and government that on one level, had been locked in a struggle with Britain throughout the 18th century, and despite France being in the throes of revolution during this period, had not abandoned their ambitions for territorial expansion.

“On the other hand, the groups [including the Garifuna] nursing long-standing grievances over British rule were not, in the first instance, concerned with France’s colonial ambitions. Their immediate aim was the redress of their grievances.” (p. 3) (the words in parenthesis are mine).

Articulated clearly in this statement was a calibre of inter-cultural political negotiation, a skill that the Garifuna had honed going as far back as their time in South America.

The high stakes political gamble that the Garifuna played with the French against the British was not successful. However, this last series of fighting had further galvanized a national character among the Garifuna for two reasons. They had fought for the lands bequeathed to them by their ancestors, both Yellows and Blacks, and in doing so they literally fought to the death, building a tradition that would forever remain among their descendants.The fixation on land as primary cause for the conflict came forward in the response of the British at the end of the war in 1797. Jacobs continued,

“In 1804, an Act was passed in the St. Vincent legislature that re-vested in the Crown the lands that they [the Garifuna] had held at the time of the Treaty of 1773. By rising in rebellion, the Caribs had forfeited all claims to their lands. The Caribs remaining in St. Vincent were later pardoned by an Act of the Legislature in 1805, but they lost all claims to the lands they formerly occupied.” (p. 11) (the words in parenthesis are mine)

While those remaining at St. Vincent lost the vigor of their cultural identity, among those coming to Central America it has flourished. However, in the aftermath of their traumatic experiences in St. Vincent, they became a nation in exile; a nation that lost its territory, sovereignty, and the political/military power to engage in alliances with other nations. Instead, they were subsumed as minority ethnic groups into emerging states and in the case of Belize, a colony of Great Britain. The question to be posed for this part of the essay is as follows. While it has been impossible for them to regain the core of their identity, namely sovereign ownership of their homeland, would they be able to retain their peoplehood?.

Although the banishment to Central America took place in 1797, it has not been until the past fifty years that their ethnic identity has been subjected to rigorous anthropological study. The people themselves have shifted in their identity from being mere appendages in often unwelcoming national societies to reclaiming an indigenous identity, which had always been theirs prior to their exile.

The analytical model of an ethnic group within the nation state has received much support from Nancie Gonzalez. Her important 1988 volume, entitled “Sojourners of the Caribbean – ethnogenesis and ethnohistory of the Garifuna”, has a Part Two entitled “The cultural basis of ethnicity” and a Part Three “The making of a modern ethnic group”. Critical to Gonzalez’s thesis is the centrality of the nation state as a society and that its parts (i.e. cultural groups) can be identified as ethnic groups. This thinking in western social science has been surpassed by the concept of peoplehood, which holds that indigenous people are a priori nations in their own right (Muehlebach (2001: 415-448).

The ideology gained widespread recognition in the 1990s and has received confirmation from the United Nations and the Organizations of American States. Apart from being appropriate to the Garifuna as indigenous people, as we have already shown in the previous phases of their evolution, the designation of peoplehood lays bare the traditional lack of acceptance in their host countries in Central America. In other words, why should they be part of a whole that either rejects them for racist reasons or accepts them, only on becoming assimilated into the national society? Gonzalez may have been alluding to this conceptual abyss when she admitted in the above volume, “In relation to ethnicity, there are in this study both theoretical and practical problems of continuing concern to many social scientists. One such problem relates to the structural position of an ethnic group vis-à-vis the larger society and what that or any other configuration may mean for the continued well-being of both. One aspect of this problem is how the individual segments of a transnational ethnic group can sustain a sense of unity.” (p. 10).

What to Gonzalez in 1988 had been a “transnational ethnic group” was actually “The Garifuna – a nation across borders”, the main title of a volume that I edited in 2005. Indeed, the acceptance of the ethnic concept in western anthropology came from a conviction that inevitably natives would have become either extinct or fully assimilated into national societies by the end of the last century. The realization that this had not taken place was the theme of Marshall Sahlins’ introductory essay in the 1999 Annual Review of Anthropology entitled “What is anthropological enlightenment? Some lessons of the 20th century” (p. i-xxiii). Having confirmed that the predictions of anthropology in the last century about the demise of native peoples had been inaccurate, he observed that many cultures had survived through their own adaptation of western technology and other aspects of the capitalist economy.

Actually, there had grown a self-consciousness of culture or “a demand of the peoples for their own space within the cultural world order” (p. x). There now is a much greater acceptance not only of the survival but also of the demands of natives to be regarded as peoples. With special reference to the Caribbean, Maximilian Forte’s edited volume (2006) presents several case studies and a wide variety of methods that anthropologists have been using in their analysis.

As in the case of any ideology attendant on a larger social movement, the acceptance of indigenous peoplehood varies among the target group. There are many Garifuna, who accept their position as an ethnic group as an immutable fact, even when the nation-state has not defined them as a people and continues to deny them such rights. I relate briefly how a group of us struggled to promote the ideology of peoplehood among the Garifuna in Belize.

The genesis was the resurgence of a Black Nationalist movement in Belize City in the 1960s in opposition to the racism within the larger colonial society. Many upwardly mobile young Garifuna men and women became members. This by itself was unusual; as they would normally be pushed within the established society into such fields as the religious ministry, teaching, or public services. The realization gradually dawned on some of us, however, that not only were we black we were also part Native American with a vibrant culture that could not be subsumed within a Black Nationalist movement. We needed to heed the call of our ancestors even as we would link with fellow blacks or other oppressed groups. Most specifically, the ancestral heritage component of Garifuna culture grabbed our attention. Roy Cayetano’s poem “Drums of Our Fathers” was symptomatic of the collective re-awakening taking place among us.

As this realization grew, a liberating exhilaration overtook us. We argued that our designation in English should not be ‘Caribs’ or ‘Black Carib’ but Garifuna, the name that our ancestors have always used for ourselves. The success of this insistence is that even in the social science literature the name changed permanently from Black Carib to Garifuna. Why should we give our children African names when we could give them Garifuna names? As a result, we compiled a list of names that we shared far and wide with those who wanted to join us in giving the ‘appropriate’ names to the next generation. Why should we dance to Jamaican reggae at parties, when we have our own drums and songs? Why should we confine our religiosity to only the western church when we also have a vibrant spirituality? Who was going to document the technologies that were quickly disappearing as masters of our crafts were dying? The same question was appropriate for our songs, dances, and folklore? Ironically, involvement in the Black Nationalist movement exposed us to the other element in us that needed re-awakening. Simultaneously, we traveled to conferences on indigenous peoples, as we conducted advocacy at home and strengthened Garifuna organizations that eventually became the National Garifuna Council. Gradually, we saw a full blown indigenous peoples organization take shape in which we – the group that started in the 1960s – are still active, if only in an advisory capacity as elders. Over time many of us took up senior level positions in teaching, university administration, religious ministry, community development, the private sector, and public service. However, our generations still retains strong interest and positions of leadership in the NGC and the international indigenous peoples' movement.

It is not surprising that this same group has left indelible marks at the world level in such areas as the regional Caribbean Organization of Indigenous Peoples, scholarly publications now being used as texts at the university level, and leading the difficult work toward the 2001 UNESCO Proclamation of the Garifuna music, language, and dance as masterpiece of intangible culture for all humanity. Even more importantly we have generated a set of new, younger, dynamic leaders to carry on the never ending work.

The achievement of this group recounted in this essay lies in capturing that indomitable spirit of Joseph Chatoyer, the military leader in St. Vincent and his fighting men and women to preserve Garifuna identity. We might have lost our territory and sovereignty as a nation in St. Vincent but we have done much to uphold the peoplehood that our ancestors in the Americas and Africa struggled to form.

This essay started with the question: “How did the Garifuna become indigenous people?”. It has shown that the Garifuna acquired the label from others in North and Central America, who were already advocating within the indigenous peoples movement in the 1980s. The historical perspective pervading this essay has shown that our friends from afar were merely re-awakening among us the indigenous peoplehood that had been the core of our cultural matrix in South America and evolved with African and European influences in the Eastern Caribbean. In short, we have been indigenous for hundreds and even thousands of years.

In this essay I have tried to review some of the processes that accompanied transformation within the Garifuna persona. At each stage the need for more research is glaring. However, having built a skeleton the rest of the work should be more easily achieved in the future.

One of the main deterrents to building lasting peoplehood is control over segments of the political economy, a point that has missed my focus in this essay, although I made reference to it in the experiences of the Island Caribs. As point of departure, we need to revisit the uncanny political acumen Garifuna ancestors displayed in the Eastern Caribbean. Even more, there is the deep struggle to continue within the same nation states that have shown a lack of empathy to the ideology of peoplehood that I have described. Fortunately, the United Nations and Organizations of American States have provided much moral and technical support. However, the next frontier, namely local empowerment through the systems of the judiciary, the legislature, the executive, local government, and public administration has to be engaged within our respective nation states by building far-flung alliances within and beyond the region.

Allaire, Louis, 1997, “The Island Caribs of the Lesser Antilles”. In The Indigenous People of the Caribbean, ed. Samuel M. Wilson, pp. 177-185. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Arrivillaga, Alfonso, 2005, “Marcos Sanchez Diaz: from hero to hiuraha – two hundred years of Garifuna settlement in Central America”. In The Garifuna – a nation across borders: essays in social anthropology, ed. J.O. Palacio, pp. 64-84, Belize: Cubola Press.

Bastide, Roger, 1972, “African Civilizations in the New World”. New York: Harper and Row.

Beckles, Hilary, 1990, History of Barbados – from Amerindian settlement to nationstate. London: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, Vincent O., 1997, “Language and gender among the Kalinago of the 15th century

St. Croix”. In The Indigenous People of the Caribbean, ed. Samuel M. Wilson, pp. 186196. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Davidson, William V., 1984, “The Garifuna in Central America: ethnohistorical and geographical foundations”. In Current Developments in Anthropological Genetics Vol. 3 Black Caribs – a case study in biocultural adaptation, ed.

Michael H. Crawford, New York: Plenum Press, pp. 13-36.

1980, “The Garifuna of Pearl Lagoon: ethnohistory of an Afro-American enclave in Nicaragua”. En Ethnohistory 27 (1): 31-63.

Forte, Maximilian C., 2006, Indigenous Resurgence in the Contemporary Caribbean. New York: Peter Lang.

Gonzalez, Nancie, 1988, Sojourners of the Caribbean – ethnogenesis and ethnohistory of the Garifuna. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Holdren, Ann Cody, 1998, Raiders and Traders: Caraibe social and political networks at the time of European contact and colonization in the Eastern Caribbean, PhD dissertation, UCLA

Honychurch, Lennox, 2002, The leap at Sauters: the lost cosmology of indigenous Grenada. UWI Cave Hill (Barbados): Grenada Country Conference.

Jacobs, Curtis, 2003, The Brigands’ War in St. Vincent: the view from French records 1794-96. UWI Cave Hill (Barbados): St. Vincent Country Conference.

Kirby, I.E. and C.I. Martin, 1972, The rise and fall of the Black Caribs of St. Vincent. St. Vincent.

Hulme Peter, 2004, “French Accounts of the Vincentian Caribs”. In The Garifuna – a nation across borders: essays in social anthropology, ed. J. O. Palacio, pp. 21-42. Belize: Cubola Press.

Miller, David Lawrence, 1979, The European impact on St. Vincent, 1600-1763: suppression and displacement of native population and landscape. M.A. thesis, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Muehlebach, Andrea, 2001, “Making Place” at the UN: Indigenous cultural politics at the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations, Current Anthropology Vol. 16 (3): pp.415-448.

Palacio, Joseph O. 2005, “Reconstructing Garifuna oral history – techniques and methods in the history of a Caribbean people”. In the Garifuna – a nation across borders: essays in social anthropology, ed. J. O. Palacio, pp. 43-63, Belize: Cubola Press.

2006, “Looking at ourselves in the mirror: the Caribbean Organization of Indigenous Peoples”. In Indigenous Resurgence in the Contemporary Caribbean, ed. Maximilian C. Forte. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 215- 23.

Rouse, Irvin, 1991, “The Taino – rise and fall of the people who greeted Columbus”. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sahlins, Marshall, 1999, “What is anthropological enlightenment? Some lessons of the 20th century”. In Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 28: pp. 1-23

Whitehead, Neil, L., 1998, Who is Carib? What is Carib society? Ethnology, Ethnicity, and History, paper prepared for the workshop on Carib Societies. Georgetown, Sept. 1998.

1988, Lords of the Tiger – a history of the Caribs in colonial Venezuela and Guyana 1498-1820. Holland: Foris Publications.

Young, William, 1971, An Account of the Black Caribs in the island of St. Vincent’s London: Frank Cass.

1 In discussing the view of some Dominica Caribs on promoting tourism on their island, Whitehead noted, “It is firmly believed that Black Caribs do not sufficiently conform to the touristic ideal of the Amerindian, and so should be hidden away, erased from the culture and history of the Caribs.” (1998)

2 The Brigands, name given to French soldiers who fought in the Eastern Caribbean in the late 18th century to restore for France islands that had been taken over by the British.