HOUSE LOT TENURE IN BARRANCO, SOUTHERN BELIZE. OPENING THE FAMILY CHEST

Dedicated to the Memory of Eulalia Arana, an avid preserver of her community history

RESUMEN: Records in private collections of rural dwellers are a significant source of information that remains untapped for ethnohistoric reconstruction. This study uses a little more than a hundred items, mainly house lot rental receipts. It starts by describing how the author was able to access the documents and overcome challenges in extracting the data. It follows with the contribution of the data to understanding house lot tenure in terms of the payment practices by villagers and the system of public lands administration; the overlap among kinship, lot tenure, and residence; and some anecdotes on the village community as part of the larger colonial society of 20th century Belize. In its analysis the paper shows that the Garifuna people are an ideal group for the study of lot tenure, having been formed through violent struggles for their lands in St. Vincent and their recurring forced movements by authorities within their communities in Central America. Finally, the data points to the critical role of women in assuming possession of house lots through de facto residence and exercising headship over household members.

PALABRAS CLAVE: records, lot, labour.

ABSTRACT: Los documentos existentes en manos de habitantes rurales constituyen una fuente significativa de información no explorada por la etnohistoria. Este estudio da cuenta de un poco más de cien documentos, principalmente recibos de renta. Inicia describiendo cómo le fue posible al autor acceder y superar retos en la extracción de datos. Continúa con la contribución de los datos para la comprensión de la tenencia de predios a partir de las prácticas de pago por parte de los habitantes del sistema público de administración de tierras; entendiéndose con ello, en mutuo acuerdo, la tenencia a través de la residencia. También se narran algunas anécdotas de la comunidad como parte de una sociedad colonial del Belice del siglo XX. En el análisis el artículo muestra que los garífunas son un grupo ideal para tal estudio, habiéndose constituido a través de violentas luchas por la tierra en St. Vincent y la recurrencia de movimientos forzados por las autoridades dentro de las comunidades en Centroamérica. Finalmente, los datos apuntan hacia un papel crítico de la mujer al asumir la posesión de los predios a través del establecimiento de la residencia y como cabeza de familia.

KEY WORDS: documentos, predios, labor.

As primary source of history, publicly available archival records usually provide macro-level information for research on nation-states and large urban communities. Caught at a disadvantage, on the other hand, are rural communities, especially small villages, usually dismissed as insignificant. Fortunately, oral history has acquired great popularity as source of information for both anthropologists and historians within the past three to four decades. While oral history, according to Kreech (1991: 345-395), has moved substantially from the degree of being unacceptable to acceptable as legitimate source in anthropology, in his thorough review of the state of ethnohistory in 1991, he mentioned hardly any word on the use of records in private collection as primary source. This paper, a review of official records in a private collection covering mainly lot receipts, provides ethnohistorical information not normally available about a rural community spanning the period 1899 to 1983. The subtitle «opening the family chest» refers to the private and personalized nature of the collection and its dedication to family matters. The paper starts with an overview of the Garifuna —formerly called Black Carib— people, who make up the majority of the population in the village of Barranco in Southern Belize, the site of this study. It continues with the research methods used to access the information, together with facing the challenges inherent within the information. There follows a narrative of the data and finally its contribution to the ethnohistory of lot tenure in terms of the payment of leasehold rent by the villagers and its receipt by public administrators; the overlap among kinship, lot tenure, and residence; and some anecdotes on the village community as part of the larger colonial society of 20th century Belize.

THE GARIFUNA: TRADITION AND FORMAL/NON-FORMAL HOUSE LOT TENURE

This study is an example of the use of information (i.e. official records) as personally selected by the original compiler. Her name was Eulalia Arana and further below I will provide more information about her. She was born and grew up in the Garifuna village of Barranco. The Garifuna are Afro-Caribbean people formed by the mixture of Maroon African slaves with Native American Carib-Arawaks in the Eastern Caribbean. There are several published sources about their formation in the Eastern Caribbean island of St. Vincent & the Grenadines; the wars with the British over their lands; their defeat and exile to the island of Roatan, Honduras; their dispersal throughout the Central American coastal countries of Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and Belize; and their current life in villages and towns in Central America as well as in North America (Davidson 1983, Gonzalez 1988, Gullick 1976, Palacio 2005). Being fully literate like the majority of her fellow villagers, Eulalia knew the value of storing government records. More particularly, she knew how vital it was to keep house lot rent receipts as they were the only record confirming rights of tenure to domestic space. In the village most persons do not purchase their lots, keeping them instead on leasehold from the government for generations, while paying annual rent. As the visible renewal of their right to stay in their houses and on their lots, the receipts were important indicators of security of tenure.

Land tenure at the level of the household has received far less attention compared to the use of farmlands for the Garifuna and other rural folk in Belize and almost certainly in other countries in Central America. An example of that type of study is Ashcraft (1965: 266-274), which looks at the family social structure within the household in rural Belize. Nancie Gonzalez’s prolonged focus on the consanguine household (1969, 1984: 1-12 and 1988) marks a culmination in the literature on household social structure among the Garifuna. Our own ongoing study of the first survey on house lots in Barranco in 1893, the clustering of family groups in contiguous lots; and the transmission of rights within kin groups for over one hundred years – all have brought house lot tenure closer to a much needed centre stage (Palacio et al. 2008 and 2009). The source of information for our studies has been records available in archives at the Lands Department and the Belize Archives Department in Belmopan, the national capital city of Belize. The content, therefore, reflects formal aspects of lot tenure.

At the village level, however, there is informal customary practice that guides normative behavior on lot tenure For example one can leave one’s house and lot in the care of a relative during trips away from the village. Such subletting of leasehold is not approved by law but the government officers turn a blind eye on this, among other «infringements» of the usufruct rights of national lease lands. There are other practices that function more at the moral level of Garifuna culture. After birth the placenta is buried in the lot, from where it exerts a mystical territorial power drawing one to one’s home village. Similarly, the preferred burial place is one’s home village, where the ancestors themselves had been laid to rest. From time to time ancestors’ spirits demand certain rituals that have to be performed in the home village. Relatives flock from far and wide, to participate from the neighboring community or as far as away as Chicago or Los Angeles.

Barranguna —the name for persons from the village or who otherwise call it home— use both the formal (i. e. legal) and non-formal (i.e. traditional) realms of lot tenure. To them paying the annual rent entitles them to remain on the lot, where in turn they can perform their traditional practices. Furthermore, the government has allowed such use in so far as it tolerates and allows customary tenure (see Palacio et al. 2009). Very rarely are tenants expelled from their lots, even after years of non-payment. From one perspective tenure has remained fairly secure over time; but it is incumbent on the payer to keep one’s receipt, in case there may be queries by government officers.

This distrust in government authority, even though at moments it might have seemed remote to Eulalia, was justified. She was a leader in the November 19th celebrations held every year in the village to celebrate the early 19th century arrival of the Garifuna in Belize as the end of a search for muñasu —a close translation in English is «refuge»—, starting with their forced exile from their homelands in St. Vincent. She would have heard from her grandparents’ generation of the several forced movements they and their parents had experienced in Honduras to escape reprisals from the authorities. The evictions continued in Belize, in one of which some of the early settlers of Barranco were driven around the 1850s from the village of Jonathan Point in the Stann Creek District. This oral tradition is repeated not only in Barranco but also in Seine Bight, another place to which the Jonathan Point refugees fled.

Within the context of traditional practices I include a brief description of disposing of personal effects of a deceased person to show how the collection in this study ended up in my scrutiny. At the funeral of a loved one, some of her smaller personal effects, such as earrings, necklace, a walking cane, and pair of glasses are interred with the body in the coffin. A few days afterwards an older member of the family will collect additional personal effects, including books, clothing, tools, and documents, and burn them. Obviously highly valuable objects, such as jewelry, are kept to be worn by a daughter, who would have given most attention to the deceased during her last days. This person would insist that locally made artifacts, such as utensils and kitchen accessories remain for her home use; the same goes for imported items, such as plates, pots, and pans.

Other items not regarded as too important, such as letters and receipts, are bundled and placed away in safe keeping, where they await a fate to be determined by family members, who over time may display decreasing interest in them. It was two such bundles in black shopping bags that came to my attention in 2007 and 2008 and became the topic of this study.

To collect information from public archives one follows certain universally accepted procedures that include receiving permission from a gatekeeper, who provides the document requested; sitting in a room to transcribe the information; and returning the document to remain in safekeeping. This orderly protocol did not apply in my acquiring access to the study documents. Indeed, a narrative on how I was able to study them introduces challenges in using private collections that the ethnographer normally does not encounter within conventional research methods.

The original compiler died and her stepdaughter kept possession of the records, who passed them to a distant relative —to whom I give the pseudonym John—, who was convinced that they had scholarly value. He brought them to my attention within a chain of reciprocal exchanges that we have had for years on preserving information, records, artifacts, and other memorabilia originating in Barranco. That the items ended up for my scrutiny was totally by chance. Firstly, it was due to John’s curiosity. Secondly, had they remained with the stepdaughter, they could have been thrown away like other older items no longer deemed important to a younger generation. Thirdly, it was fortunate that they were bits of paper. Had they been material objects, such as wooden bowls, wicker baskets, reed mats, and other Garifuna artifacts, they could have been sold within a growing antiquities market in Belize City. The government of Belize has laws that protect older documents but these laws are unknown by most persons. Regretfully such collections continue to be lost, robbing posterity of much information. The value of this cache of data has as information was gleaned from it and made available to the larger reading public.

The method of acquiring access was only one of the challenges to conventional ethnography that I had to overcome. The second came from the state of the medium of documentation, notably the types of ink, paper, together with the damp environment in which they had been kept. Surprisingly, only a few were completely indecipherable, although many were frayed, torn, and discolored. I was able to scan most of the items and enlarge the digitized image to better see what had been written. We have to remember that what eventually remained had been preserved in moving from one part of the village to the other or from such misfortunes as hurricanes, rodents, and leaking roofs.

A third challenge resulted because they were written to satisfy the writing style of the bureaucracy at a given time, and not the needs of a future researcher. The text on lot receipts, which made up most of the items, included lot number, location, date, the reason for payment, and the signature of the payer. In many cases there was only a signature which was not meant to be easily deciphered by members of the public. In some cases the name of the payer was not included. Both names of the collector and payer are important bits of information in completing the analysis of persons involved in the transactions being entered.

The availability of the data was due to the safekeeping diligence of Eulalia Arana, who kept them throughout her lifetime. Who was she and within what larger context was she fuctioning? In answering these questions I take advantage of additional biographical information and lot transmission records, which I have collected as part of a group study on the history of lot tenure in Barranco.1

During my dissertation fieldwork in Barranco in 1979 and 1980 Eulalia was one of my most enthusiastic informants about all aspects of village life. She had incredible recall of information and made associations, holding her own in discussions that could last for hours on end. Her eyes would light up as she drove home a point and would punctuate it with a grin followed by an infectious chuckle. During all the hours that we spent together she never revealed to me that she kept records in her collection.

To a large extent the wide assortment of items in this collection revealed the intellectual curiosity I remembered about her. About half of the bulk consisting of personal letters she had received from her offspring’s and children she had raised, who had relocated to other parts of the country or the United States. The topics were private family matters revolving around cash remittances, errands to be carried out in the village, building projects, the well-being of children and older relatives, etc. Also included in the pile were non-familial miscellanea, such as school report cards, programmes of events at school activities, pages from textbooks, lottery tickets, membership card in a political women’s group, and so on. I did not make any effort to categorize these materials as my attention was focused on the non-personal official records listed in Table 1. The events covered in the receipts were those that mattered most to her and the names on the receipts were no doubt for persons whom she most favored within her network. The names and her family relations with them are seen in Appendix 3. From her natal family the names include her father Alejandro Arana, mother Gregoria Bermudez Arana, and sibling Narciso Arana. Pre-dating the records for her natal family were two from Liborio Martinez going back to 1899 and 1909. He was her father’s mother’s close relative. Eulalia was born in 1906 so she must have found these within the family collection, which indicates she continued a practice of safeguarding receipts, which was already established in her family going back to the late 1800s. Her nuclear families revolved around three men, who were her spouses. The eldest of her children was Julio Martinez. There is no need for anymore mention of him as his name did not appear on any official record. On the other hand, there were fifteen receipts in the name of Nicholasa Martinez, his daughter with Eulalia, who lived in lot 103 (see Table 4). The second was Jose Velasquez to whom she married in 1934, when she was 28 years old. Jose had Lot 122 in his name for which he paid rent from 1934 to 1942; besides, these receipts were in Eulalia’s collection. Eulalia also had another lot, No.123, in her name adjoining Jose’s for which she paid rent from 1942 to 1981 (see Table 4). It is interesting to note that although they were man and wife, they both had lots in their separate names. Since there is no overlap during the time when both lots were being paid for, it is possible that Jose and Eulalia stayed together in the lots successively. Besides, it was not unusual for women to have their own lots separate from their husbands.

The third spouse was Bonifacio Ramírez to whom she got married in 1968. Like Julio there was no receipt in Bonifacio’s name. The irony here is that Eulalia lived with him for decades in Lot144 for which there were no receipts. This lot was registered in his name.

On the other hand, there was one receipt in 1943 in the name of Eustaquia Arriola for Lot 54. Eustaquia was Bonifacio’s mother. There was no apparent logic to account for a receipt to be in the pile for Bonifacio’s mother but none in his name, who was Eulalia’s husband. There are two possible explanations. One is that the collection at our disposal may have been disturbed, with some items getting lost. The other is that Eulalia might have had her own reason, to which we are not privy, why she kept some receipts and not others.

The larger context overtaking our compiler of records was one of an expanding socioeconomy predicating the need for more village population and more lots, spanning a large part of the first half of the last century. Eulalia was born in 1906, fourteen years after the first cadastral survey of Barranco, which officially allocated possession of lots. This act of consolidating formal ownership sent a signal that the government was serious in providing lot tenure to the villagers. Around 1906 the first banana boom period was beginning to wane but men and women had already been lured to come to settle in the village from neighboring communities. As a result, the government demarcated more lots between 1928 and 1930. Eulalia moved away from the longer settled central part of the village onto the newly available ones. By the 1950s the economy had already started to contract and lot owners left the village starting with the last settled lots in the periphery. Eulalia herself moved back to the village centre, so also did her daughter Nicholasa. But they did not stop paying rent for their unused lots. In other words, fluidity within the community did not mean the complete abandonment of house lots.

The serendipity of my receiving the documents was matched only by what I found as I proceeded from one layer of discovery to another. I separated 117 pieces that fall into three categories as seen in Table 1. They are papers on «Land Tenure», which made up the bulk, «Agriculture», and a third category «Other». There were ten documents that were not payment receipts but related to tenure. Three were reminders to pay rent and one a cancellation of lease for non-payment. One was a court fee for non-payment of rent and two court summons for rent non-payment. One was rent assessment for farmland and the other an application to lease a lot. Finally, there was a copy of the conditions for «Location Ticket for Crown Land».

Table 1. Types of Documents

Frequency |

Year |

Types |

Comment |

|

|

Land Tenure |

|

89 |

1899-1983 |

Receipts for Rent of Lots |

Make up most of the collection |

10 |

1945-1981 |

Receipts for Crown Land Location Ticket |

|

1 |

1940 |

Court fee for non-payment of lot rent |

|

1 |

1973 |

Cancellation of lease |

|

2 |

1939 and 1947 |

Court summons for rent non-payment |

|

1 |

1955 |

Rent assessment for farmlands |

|

1 |

1964 |

Application to lease lot |

|

1 |

1920 |

Lease renewal |

|

1 |

1944 |

Reminder of due rent |

|

1 |

1951 |

Final reminder of due rent |

|

1 |

1954 |

Conditions for Location Ticket |

|

|

|

Agriculture Related |

|

2 |

1955 and 1956 |

Marketing Board Voucher |

Government agency to buy rice |

1 |

1964 |

Permit to set fire to milpa (bush garden) |

|

|

|

Other |

|

1 |

1968 |

Hospital fee |

For attention in town hospital |

1 |

1944 |

School Absence Fee |

To parents for child’s absence |

1 |

|

Certificate of Health |

To work in certain occupations |

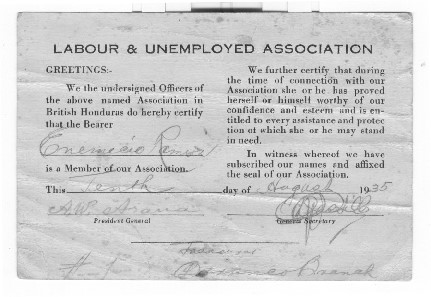

1 |

1935 |

Labour and Unemployed Association |

Membership fee for Barranco Branch |

1 |

1901 |

Passport |

British colony citizen |

Total No. of Documents 117 |

|

||

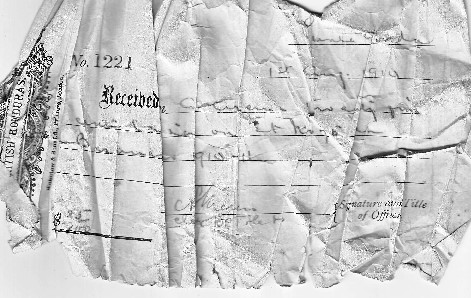

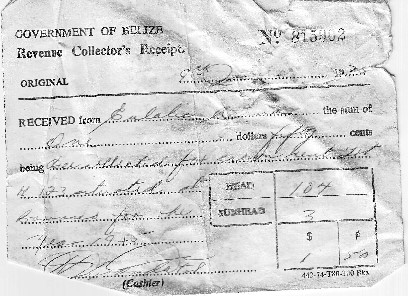

The largest number of any item was lot rental receipts, totaling 89 and ranging in time period from 1899 to 1983. Up to 1922 there was no prescribed format; and up to 1914 the rent was called ‘land tax’ typed onto the receipt, everything else being in long hand. In Appendix 1 there is a copy of this type of receipt. By 1931 the government was using a prescribed format with specifications seen in Table 2. By 1943 the ‘lease application number’ was inscribed on the form, making it easy to trace when the lease was first issued. However, by the 1950s this addition was taken away. Another modification over time was changing «Collector» to «Cashier». There is a copy of the 1950s format in Appendix 2.

Table 2. Specifications on Lease Lot Receipts

Date of Issue |

Received From |

Amount in text |

Year of Rent |

Lot Number |

Location of Lot |

Lease application Number |

Amount in Number |

Name of Collector |

Signature of Payer |

From 1941 the momentum of collection picked up considerably as seen in Table 3.

Table 3. Frequency of Lot Payment by Decade

Decade |

Frequency |

|

Cumulative Frequency |

Cumulative Percentage |

<1901 |

|

1 |

|

|

1901-1910 |

|

1 |

2 |

4.2 |

1911-1920 |

|

8 |

10 |

11.3 |

1921-1930 |

|

4 |

14 |

14.1 |

1931-1940 |

|

8 |

22 |

23.9 |

1941-1950 |

|

13 |

35 |

38.0 |

1951-1960 |

|

20 |

55 |

63.3 |

1961-1970 |

|

16 |

71 |

80.2 |

1971-1980 |

|

16 |

87 |

97.2 |

1981-1990 |

|

2 |

89 |

100.0 |

Among the eight lease holders, Eulalia Arana recorded the largest number of payments at 30, with Narciso Arana second at 19, and Nicholasa Martínez at 15. One of the earliest lease holders was Liborio Martínez, who paid for Lot 75 in 1899 and Lot 28 in 1909. There is more information in Table 4.

Table 4. Chronology of Lease Holders

Name |

Year |

Lot No. |

Frequency |

Liborio Martínez |

1899 |

75 |

1 |

|

1909 |

28 |

1 |

Alejandro Arana |

1912-1940 |

75 |

13 |

Gregoria Arana |

1922-1931 |

75 |

3 |

Narciso Arana |

1944-1983 |

75 |

19 |

José Velásquez |

1934-1943 |

122 |

6 |

Eulalia Arana |

1942-1981 |

123 |

30 |

Nicholasa Martínez |

1953-1972 |

103 |

15 |

Eustaquia Ariola |

1943 |

54 |

1 |

Total |

|

|

89 |

From 1899 to 1983 the annual rent paid was $1.50 per lot. In 1916 and 1918 a lease should pay in installments of $0.25 but in subsequent years he paid in full for the year. Although the payer could enter his signature, instead of writing his full name, in most cases they wrote their full name, making it easier to decipher who actually paid. In most cases it was not the actual leaseholder. At that time the only way to reach the district of Punta Gorda was by boat, so it may have been a boat captain. The name of Ruben Palacio, a captain well known for his legendary kindness to help villagers, was recurring as payer. The payer could be a village officer going to town on official duties. The names of such persons include the alcalde, the elected village headman, or the resident Deputy Registrar of Births. In the latter case the name of I. Nicholas was recurring. From 1960 the policeman stationed in the village collected the rent. The identity of the policeman can be deduced from his number, which was appended to his signature. There was a noticeable pattern in the timing of payments by Eulalia Arana. She did her annual payment usually in June or July of every year starting in 1955.

ETHNOHISTORICAL CONTRIBUTION

PUTTING A HUMAN FACE TO LAND ADMINISTRATION

From the 89 records on lease rental it is possible to spotlight the system of payment as a two-way transaction featuring the payers and collectors. Earlier we saw that there was strong feeling of obligation to pay the annual rent and to retain the receipt as symbol of security of tenure. So strong was this compulsion that Eulalia paid her 1946 rent ‘by post’, according to the receipt. The time to pay no doubt caught her away from the village and she did her next best, which was to send it through the post office. Notwithstanding the spirit of duress, in most cases the actual payment took place under the veil of friendly relations so typical of most interactions within the village community. I need to emphasize that the relations underlying the payment certainly was not duplicated in actually earning the money to pay the rent. Although the amount appears small by today’s standards, it demanded much work to accumulate.2

The office for payment was in the neighboring town of Punta Gorda located twelve miles by sea until a road became passable in 1998. Before the road made transportation to and from the village much easier, in many cases the payer did not go into town and instead would ask a friend or relative to do the favor. Performing this role of intermediary was often the friendly boat captain, well known for doing this among tens of errands for his fellow villagers on any one trip. After 1960 they could do their payment directly to the policeman stationed in the village, who became another party to a transaction that had always been through intermediaries.

Barranguna kept up this framework of interactivity with the public administrators, who collected the rent, using the cultural bond of Garifunaduo —loosely translated as Garifunaness— . Deciphering the names of the «Collector», later called «Cashier», on the receipts was not always easy as these bureaucrats more often signed a signature better known in their own circles than for public information. I was able to identify the following names found in chronological order –A.S. Marin, Benguche, M. Arzu, Colon, C.F. Apolonio, Benito Arzu, and Avila, as Garifuna. At least one of these men, A. S. Marin, later came to teach in Barranco and married a Barranguna. Villagers mentioned some of the others as having been helpful with lot payments and other transactions These men presented a human face and identity as fellow Garifuna that helped to bridge the gap between the public administration system and the village community.

Among the three topics of kinship, lot tenure, and household residence, only kinship has received much attention in Garifuna studies. Inevitably, the focus on the information found in these records has integrated into kinship lot tenure and household residence, two topics that need much attention. Because of the limitations of the data, it is premature to arrive at patterns; however, I can pinpoint some leads that could be followed up when more data becomes available.

One such lead falls under the heading of transmission of rights to lots, arising from transfers from Liborio Martinez to Alejandro Arana, from Alejandro Arana to his wife Gregoria, and from Alejandro to his son Narciso –all taking place in Lot 75. There is need for a caveat before going into details. It is that at death there are cultural norms that determine who the house and lot should go to, although in most cases Garifuna men and women die intestate. For more information see Palacio, Tuttle, and Lumb (2009). The following discussion shows that contrary to the statement that lots and houses are transmitted through bilateral (i.e. mother’s and father’s lines) (Gonzalez 1969: 578-583), actual transmissions can take their own permutations.

Liborio’s transfer to Alejandro came through a kinship tie of Liborio’s mother, who was a close consanguine of Alejandro’s mother. This can be classified as flowing through the maternal link of both men and could fit the designation of one line of descent (i.e. mother’s), where putatively it could also go through the paternal tie, therefore displaying one form of bilateral descent.

On Alejandro’s death, his wife continued to pay the rent, making her the de facto person in charge, with her name appearing on the receipt as payer. The next person to pay the rent for Lot 75 was Narciso Arana, son of Alejandro and Gregoria. What do we make of this sequence of transmissions starting with a man, continuing with his wife, and ending with their son? A search in the official lot registry records sheds some light.

According to the official lot ownership records, Narciso Arana took possession of Lot 75 from his father in 1940. There is no mention of his mother ever being a formally registered owner, although she was paying rent and receiving receipts from 1922 to 1931. The suggestion forthcoming is twofold. One is that Gregoria was de facto head of the household and payer of the rent, no doubt after the demise of her husband before 1922. She did not, however, proceed to apply to have the lot registered in her name. The other suggestion is that actual residence is not necessarily reflected in de jure registration. Or that what states in the ownership records is not necessarily the same as that on the ground. The receipts, therefore, help to clarify daily reality within lot ownership. And the reality for Gregoria was the need for her to pay the annual rent to avoid losing the house and lot that she and her husband had maintained for some years for the benefit of their children.

The responsibility that Gregoria displayed in maintaining her house and lot until her son could take over the payment reflects the pivotal role of women in village lot tenure, although there is no commensurate recognition forthcoming in terms of becoming registered owners. In other cases, women do retain ownership of lots in their own name, although they are married. I refer again to Eulalia having her own lot adjoining her husband and that she paid for hers while he paid for his. While displaying this relative independence, Eulalia lived for decades in her other husband’s lot, while she continued paying for her own lot. It’s important to note that the community allows women a wide range of options in lot tenure, which they can apply as they see fit.

Apart from the analytical reflections on lot tenure derived from the receipts, there were other conclusions forthcoming from other data in the collection. These, however, are more of an anecdotal nature. I include them more to show how little information is available in Belize on rural villages as part of the larger colonial society during the 20th century and how much can be gleaned through private collections that may not reach the public archival sources.

1. Passport. In 1901 Alejandro Arana acquired a passport as citizen of a British colony.

2. Labour and Unemployed Association. In the mid 1930s Antonio Soberanis formed a militant grassroots organization to exert demands on colonial government for better living conditions (Shoman 1994: 186). The organization called the Labour and Unemployed Association formed a Barranco Branch that included as member Enemencio [sic] Ramirez.

He was assigned a card, a copy of which is found in Appendix 3.

3. In 1940 Eulalia Velasquez received a ‘Certificate of Health’ which stated, «I … find him» [sic] to be free from any active manifestations of infectious or contagious diseases, and is in a fit state of health to be employed as baker in the town of Punta Gorda. The certificate informs not only about the state of health but also about Eulalia’s interest to work as baker at that time in the neighboring town of Punta Gorda.

4. School Absence Fee. In 1944 the village alcalde S. Benguche issued a receipt of $.50 to Eulalia Velasquez as fee for the absence of her daughter from school for five days. The receipt has clearly printed in bold font «General Revenue Receipt Valid for Receipts for School Fines», showing that the alcalde was acting within his legal duties in imposing the fine.

5. Marketing Board Purchases. The Marketing Board was a statutory organization that bought agricultural produce from farmers. In 1955 Bonifacio Ramirez received $.26 for

the sale of four pounds of rice paddy. The following year Eulalia Arana sold 35lbs and received $1.36. In Eulalia’s voucher there is a note saying that government was buying rice paddy at $3.90 for hundred pounds.

6. Hospital Fee. Eulalia Arana received a receipt for paying $8.00 as Hospital Fee in 1968. The type of service was not included but it was no doubt for medical attention she received at the town hospital.

Although there has been little study of house lot tenure among the Garifuna, they are a prime target for such a focus. Their house lot possession is split between formal and non-formal domains. Under the former they receive access from government authorities but their actual possession is mediated through the latter, mainly traditions based on beliefs in the demands of their ancestral spirits and the territorial bind from the placenta buried in the lots of their birth. Finally, they maintain a collective experience kept alive through oral traditions of exile from St. Vincent and evictions in Central America leading to several attempts to find suitable lands for settlement. All of these experiences augment to them the value of paying the annual rent for their lots and keeping the receipts.

The research methods in this study differ from those traditionally used in the field, especially in acquiring access to the information. While ethnographers usually have direct access to archival records, I had to capitalize on a previously formed reciprocal framework of exchanges in village memorabilia to be able to access the records. Besides, before digitizing the records, I had to overcome challenges derived from the heavily aged bits of paper. Finally, I had to overcome the limited nature of the information, whose content had originally been designed less for research than for bureaucratic purposes.

The profile of the compiler came alive from my earlier experiences with her as a model field informant. The chronology of the records revealed that she inherited the collection from earlier family members and assiduously added to it. The several strands of her natal and nuclear families provided several groupings of lot rent receipts. In all there was a total of 117 documents, excluding a large bulk of mainly personal letters. Within the village itself fluctuations in the economy during the first half of the last caused increases and decreases of the population as well demanded for more lots and more mobility.

The ethnohistorical contributions in the analysis of the data vindicates the usefulness of this cache of private records, especially in bringing to light village-led transactions that normally would not appear even in the government archives. The information, for example, that Gregoria Bermudez Arana paid rent for Lot 75 from 1922 to 1931 showed how she took the lead to preserve the lot in the family possession after the death of her husband and before her son could assume the responsibility. This relatively small but significant bit of information amplifies our understanding of the link between house lot transmission and de facto residence. Finally, there are some anecdotal tidbits that add to an appreciation of village community life during the colonial era of the last century.

Ashcraft, Norman, 1965, «The domestic group in Mahogany, British Honduras». Social and Economic Studies of the University of the West Indies, vol. 15, núm. 3, pp. 266-274. Jamaica.

Davidson, William V., 1983, «The Garifuna in Central America: ethnohistorical and geographical foundations». Current Directions in Anthropological Genetics, vol. 3, ‘Black Caribs–a case study in bicultural adaptation’, pp. 13-36, it published by Michael H. Crawford. Plenum Press, New York.

Gonzalez, Nancie L., 1969, «Black Carib Household Structure – a study of migration and modernization». University of Washington Press, Seattle.

1984, «Rethinking the consanguineal household and matrifocality». Ethnology, vol. 23, núm. 1, pp. 1-12.

1988, «Sojourners of the Caribbean – ethnogenesis and ethnohistory of the Garifuna».

University of Illinois Press, Chicago.

Gullick, C.J.M.R., 1976, Exiled from St. Vincent: the development of Black Carib culture in Central America up to 1945. Progress Press, Malta.

Kreech III, Sheppard, 1991, «The state of Ethnohistory». Annual Review of Anthropology. vol.

20, pp. 345-379.

Palacio, Joseph O. (ed), 2005, The Garifuna – a nation across borders: essays in social anthropology. Cubola Productions, Belize.

Palacio, Joseph O., J. R. Lumb, and C. J. Tuttle, 2008, «The power of the survey line – the first lot survey in Barranco». Southern Belize. Paper presented at Vera Cruz.

Palacio, Joseph O., C.J. Tuttle, and J.R. Lumb, 2009, «Lot Transmission in Barranco, Southern Belize 1893-2000: ownership and relations underlining succession of ownership». Paper to be presented at the International Congress of Americanists Meetings in Mexico City.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

1975 Receipt to Eulalia Arana, Cashier (name indecipherable) Note the presence of formatting, unlike Appendix 1

Appendix 3

Chart I

Kinship Charts - Legend

Chart 1 Alejandro Arana and Gregoria Arana

Alejandro Arana got lot No. 75 from Liborio Martínez. Afterwards his son Narciso got it.

Chart 2 Eulalia Arana and José Velásquez

Eulalia Arana’s first husband was José Velásquez. He got lot No 122 and she got lot No 123.

Chart 3 Julio Martínez and Eulalia Arana

Julio Martínez had a daughter by Eulalia Arana. She was Nicholasa Martínez who owned lot No 103.

Chart 4 Eustaquia Ramírez Arriola and her son Bonifacio Ramírez

Bonifacio Ramírez’s mother Eustaquia Palacio married Bonifacio’s father Carmen Ramírez and subsequently married Patrocinio Arriola. Eustaquia lived on lot No 54.

Appendix 4

Fecha de recepción: 23 de febrero de 2009.

Fecha de aceptación: 11 de julio de 2009.